Gaetano Chierici was responsible for amassing the oldest ethnographic core collection in the Reggio area (on display in the “Gaetano Chierici” Museum of Palethnology). He did so when an interest in peoples living outside of Europe arose within the cultural milieu of emerging prehistoric studies, as inspired by the evolutionist concept of human history. The collections of ethnographic materials, which continued to reach the Museum even after Chierici’s death (1886), are now shown in a new exhibition arrangement (1999) which supplements the Reggio Collection with collections acquired in 1970 from the National Archaeological Museum in Parma, thanks to the efforts of Giancarlo Ambrosetti.

Reusing pre-existing display space with IXX Century enclosures, the exhibit path begins with American collections known as the Vincenzo Bonini Collection (1903-11) and the Luigi Luiggi Collection (1895), both containing material from Tierra del Fuego in Argentina (a bow, arrows, quiver and cape made of guanaco skins from the Onas, and two harpoons made by the Alacalufs). The materials from the Amazon were collected by members of the Schivazappa family. Consular agent Enrico Schivazappa provided items (1883-1888) associated with the Crichana, the Uaupés-Tucano, the Paumari, the Ticuna and the Jivaro, while grandchildren Enrico and Armando are credited with materials collected mainly from the Carajà (1896-98). The most copious group of objects are from the Crichana on the Rio Yauaperì (a tributary of the Rio Negro) and include ornaments, arms, musical instruments and a terracotta bowl. The Paumari, on the Rio Purùs, originated the small canoe, combs and group of retiform ornaments – important examples of feather art.

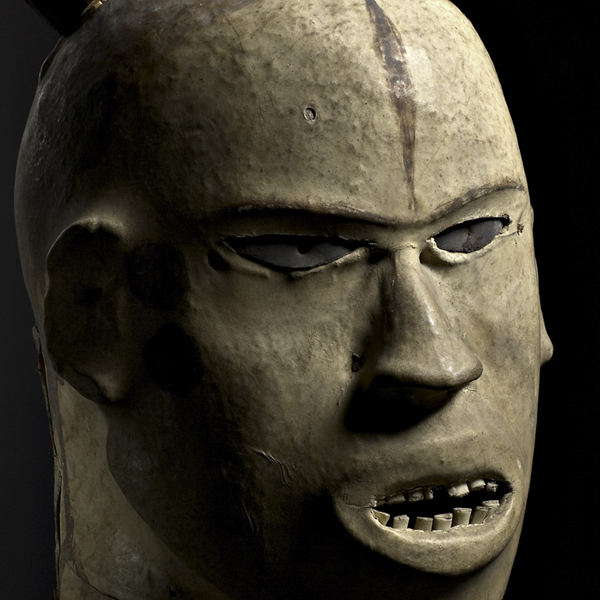

Worth special mention are the masks made of ground, beaten tree bark that were used in female puberty rites by the Ticuna on the Rio Solimões. The Jivaro, who lived on the Rio Santiago in the Peruvian Amazon, were responsible for the shrunken head (tzantza). The Karajà and other peoples on the Rio Araguaja crafted the painted paddle, arms, ornaments, crockery and pipes. Next come the pre-Columbian archaeological collections, with Peruvian vases by the Chimù (1000-1450 A.D.) in the Collection from the Public Library. The Peruvian archaeological materials, gathered by Enrico Mazzei (1884), are from the central Peruvian coast and include manufactured items made of textiles, a utility basket containing spindles and small skeins, and the upper part of a mummy along with finds from the Mesoamerican and Colombian area that comprise minute decorations in jadeite (collected by Eleonora Dall’Omo) and small figures in clay (collected by Luigi Bruni, 1901-8). Worth special mention is the pendant made of jadeite called ave-pico which is associated with the area of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The exhibit continues with Abyssinian materials that were collected by Captain Vincenzo Ferrari (1885) and entered the Museum after Chierici’s death, and with various collections from Abyssinia (Corti 1914, Calderoni 1936, Iotti 1950, Cardarelli 1956). Four collections realised by Baron Raimondo Franchetti in Asia and Africa are placed in the enclosures above the African hunting trophies of this explorer from Reggio. The first contains materials from the Indonesian area of Malaysia, Java, Borneo, Sulawesi and New Guinea. In 1911, upon returning from an adventurous trip (in Europe, he was given up for lost), he donated to the Museum a number of arms, garments, musical instruments and furnishings, including interesting arms from the Sakai and the Dayak. Placed among these are objects from the Dall’Omo collection, featuring precious krisses. Next we find the 1912 collection from the Moi peoples of Annam, which consists (among other things) of crossbows, arrows kept in bamboo quivers, baskets for rice, pipes and two beautiful combs. Franchetti brought back material from his African trips for two abundant collections. From the Shilluk people (1913) in the upper Nile come not only arms, but also elegant pipes, a headrest and precious bracelets in ivory. Perhaps the richest in arms and shields is the rather massive 1914 collection of materials from the Kikuyu and Meru peoples in Kenya. Among the arms, however, we again find objects that reveal other aspects of the life of these peoples, who speak a Bantu language. These include belts with cowries and pearls made of glassy paste, wooden earrings, silver rings, ivory amulets, wooden stools decorated with metal inserts, and gourds for carrying water. Next we find the African collection of the Marchis, which was developed in the Congo basin (1928-1933). It mostly deals with the Luba people and consists mainly of arms. Finally, a recent addition (2011) to the ethnographic section are materials that comprise the collection of Giuseppe Corona. It, too, was kept at the Parma Museum of Antiquities until the early 1970s. This interesting core group of manufactured items includes a significant series of wooden statues which was published by Ezio Bassani. Knight Giuseppe Corona, the Italian consul in the Congo, had been engaged by the Italian Foreign Ministry to write a report on economic development in that region. During a trip along the Congo River (1886 –1887), he was able to acquire a host of materials that were purchased by the Pigorini Museum in Rome in 1889. Following a number of trades and donations between Luigi Pigorini and Giovanni Mariotti, the Director of the Parma Museum of Antiquities, these objects ended up in Parma, and from there they were subsequently transferred to the Musei Civici in Reggio Emilia.