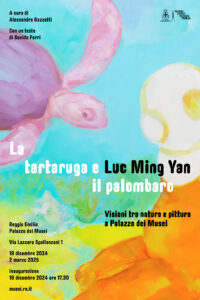

A cura di Alessandro Gazzotti con un testo di Davide Ferri

Reggio Emilia, Palazzo dei Musei, 19.12.2024 – 2.03.2025 prorogata fino al 9 marzo 2025

Giovedì 19 dicembre alle ore 17.30 è stata inaugurata la mostra Luc Ming Yan. La tartaruga e il palombaro. Visioni tra natura e pittura a Palazzo dei Musei.

Il dialogo costante tra archeologia, arte, fotografia e scienze è uno degli obiettivi principali del nuovo Palazzo dei Musei, che si propone di utilizzare le sue raccolte per lasciare aperte le infinite variazioni narrative, poetiche e scientifiche che potenzialmente offrono alla cultura contemporanea. Nell’idea che anche gli artisti, come gli studiosi e gli esperti delle varie discipline, possano utilizzare come fonti e come strumenti di analisi le collezioni dei Musei Civici, si promuovono forme di collaborazione che stimolino sguardi nuovi e inattesi. In questo senso l’incontro che il giovane artista francese Luc Ming Yan ha avuto col nostro museo, e in particolare con le collezioni naturalistiche della Collezione Spallanzani e delle raccolte di zoologia e di anatomia, ha generato un’immediata risonanza, concretizzatasi poi in una mostra che apre un dialogo e una riflessione tra natura e pittura.

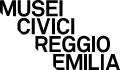

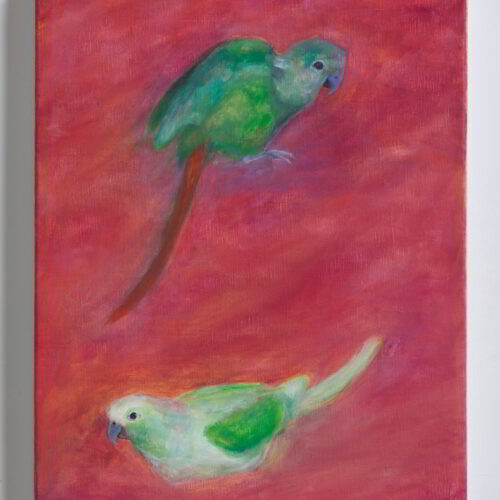

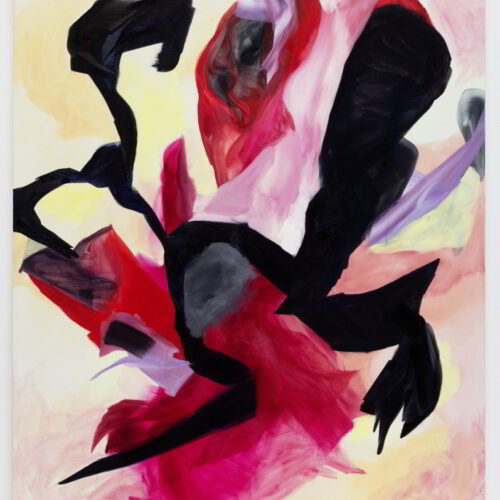

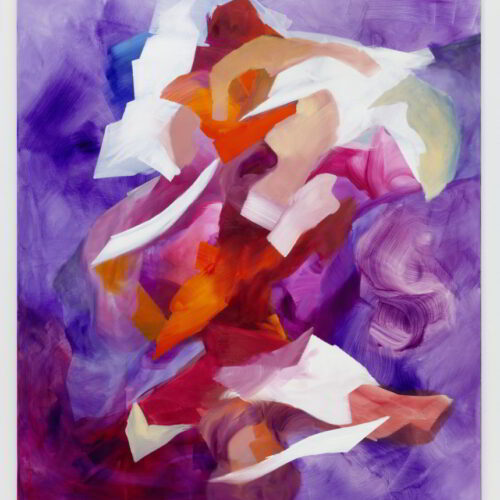

La mostra, a cura di Alessandro Gazzotti, presenta 48 opere dell’artista nato a Digione nel 1994 e attivo tra Parigi e Shanghai; 48 oli su tela caratterizzati da una grande varietà stilistica e da un gusto particolare per il colore che lo rendono un autore originale nel panorama della pittura contemporanea. Le opere dialogheranno direttamente con le collezioni naturalistiche, in particolare con il grande fossile di balena “Valentina”, fondamentale ritrovamento pliocenico del nostro territorio, in uno stimolante confronto. La mostra è inoltre accompagnata da un testo di Davide Ferri, curatore e critico d’arte, docente dell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Bologna e nominato da poche settimane nuovo direttore artistico di Arte Fiera, appassionato al lavoro di Yan. Scrive Ferri: “la partitura si sviluppa, di sala in sala, attraverso l’accostamento di questi due versanti del lavoro di Luc Ming Yan. Da una parte lavori che mostrano un magma, un nucleo denso di pennellate convulse, movimentate e contrastate, dall’altra lavori marcatamente figurativi, dove appaiono animali (come ratti, volatili, scimmie, gatti), teschi, figure metamorfiche, aliene, vagamene mostruose, che sembrano provenire da un immaginario contaminato da suggestioni manga o pop. Non solo: elementi pre-figurali, brandelli di forme (come zampe, corna, o artigli affilati) possono apparire anche all’interno dei dipinti astratti, dando l’impressione di scaturire da quel magma fecondo e generativo, posizionandosi ai bordi o appena fuori da questo. Come se in quei lavori fosse in corso un combattimento con l’immagine, e proprio l’energia concitata che occupa la superficie fosse il luogo in cui hanno origine tutte le forme e le figure dei suoi dipinti”.

Luc Ming Yan (1994, Digione, Francia) è un pittore francese che vive e lavora a Digione. Dopo aver ricevuto il Premio Ernest Manganel e aver completato gli studi presso la Scuola di Belle Arti ECAL di Losanna, in Svizzera, i dipinti di Yan sono stati esposti a livello internazionale. Tra le mostre recenti si ricordano: Abstraction (re)creation – 20 under 40, Le Consortium, a cura di Franck Gautherot e Seungduk Kim, Digione, Francia (2024); The Drawing Centre Show, Le Consortium, a cura di Franck Gautherot e Seungduk Kim, Dijon, Francia (2022); Ipotesi Astronomiche, Villa Flor, S-chanf, Svizzera (2021); Stasi Frenetica, Artissima Unplugged, MAO – Museo d’Arte Orientale, Torino, Italia (2020). Nel 2024 i lavori di Yan Midnight (2023) e Time Walk (2023), esposti durante la mostra collettiva Abstraction (re)creation – 20 under 40 sono entrati nella collezione permanente di Le Consortium.

I lavori di Luc Ming Yan, in particolare quelli inclusi in questa mostra ai Musei Civici di Reggio Emilia, dal titolo La tartaruga e il palombaro ti fanno guardare, diciamo così, da una parte e dall’altra. Dalla parte cioè di dipinti che non saprei chiamare altrimenti se non astratti – con coaguli di campiture e pennellate spesse, instabili e multidirezionali, che si avviluppano vorticosamente al centro dell’immagine – e dalla parte di dipinti più evidentemente figurativi in cui affiorano figure mostruose, aliene, metamorfiche, antropomorfe, animali (selvatici, come ratti e volatili, o domestici, come il gatto e la gallina), o semplicemente pop e fantasy, che sembrano sbucate da un fumetto, un anime o un videogame. Così è costruita la mostra di Reggio Emilia: come una partitura in cui quelli che hanno tutta l’aria di essere i due lati del lavoro dell’artista procedono fianco a fianco dalla prima all’ultima sala.

Detto tra parentesi: inizio questo testo dicendo “astratto” e “figurativo”, e nel farlo ne avverto immediatamente il suono obsoleto. È giusto tenere ancora in contrapposizione queste due categorie storiche? È semplicemente inevitabile quando si parla di pittura? Non farei invece meglio, fin da subito, a dire che proprio alcuni pittori, come del resto anche Luc Ming Yan, da qualche decennio a questa parte, hanno saputo evidenziarne il confine poroso, fino a trasformarle in categorie vicine, perfino sovrapponibili e intercambiabili?

Gli spazi del museo di Reggio Emilia in cui si svolge la mostra non sono certo un white cube. Al contrario sono fortemente connotati, per via della stretta prossemica con le collezioni (una parte della mostra si svolge proprio all’interno di teche e vetrine dove la collezione è esposta), che hanno una specificità molto forte: una serie di raccolte naturalistiche, anatomiche, botaniche ed etnografiche.

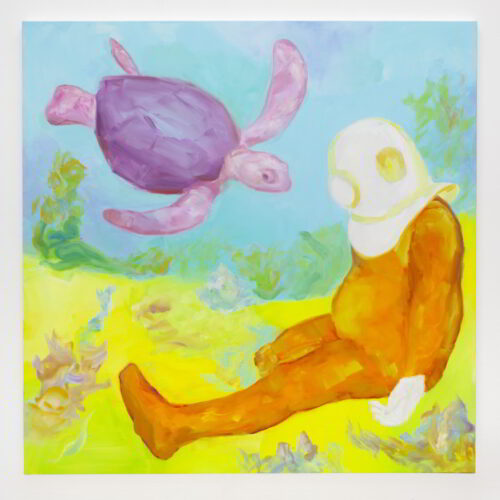

Da questa eterogeneità, da una collezione che è wunderkammer e gabinetto di curiosità, campionario di animali tassidermizzati, ossa, scheletri e reperti di vario genere, Luc Ming Yan sembra quasi essersi lasciato sollecitare: i suoi dipinti con figure, ad esempio, mostrano animali comuni o preistorici, fantastici o estinti, bestie deformi ed eccentriche (come uno scheletro di un dinosauro con due crani), ma in generale tutte le figure della sua pittura entrano a far parte di questo bestiario. Alcune immagini dell’artista sono inoltre sottese da un senso di palpabile minaccia, con qualche richiamo più scoperto alla morte: il teschio è soggetto di una serie di lavori, in un dipinto un cadavere di passerotto campeggia in primo piano accanto a un gatto nero che è presumibilmente il suo carnefice; il lavoro che dà il titolo alla mostra, La tartaruga e il palombaro, rappresenta un incontro tra un sommozzatore e una tartaruga nella profondità marina. Il palombaro è inerme, forse morto, il capo e lo scafandro marcatamente reclinato, un palmo rivolto verso l’alto, in segno di resa, il corpo gonfio. La tartaruga, in un gioco di ruoli invertito, sembra esplorare, e avvicinandosi all’intruso lo sorveglia.

Ma torniamo ai dipinti astratti. Ho cominciato descrivendo, fin qui, alcuni dei soggetti in mostra, ma il punto è che via via che lo sguardo si adatta ai dipinti di Luc Ming Yan, queste due parti del suo lavoro – quella astratta e quella figurativa – iniziano ad apparire come vasi comunicanti e, in un certo senso, assai più vicine di quanto non appaia a un primo colpo d’occhio.

Ogni suo dipinto astratto, l’ho già detto, è un coagulo vorticoso di campiture e pennellate, tratti volatili e multidirezionali, che tendono ad addensarsi e sovrapporsi in una massa centrale, o ad attraversare la superficie in senso verticale o diagonale. Sciami di pennellate, campiture e macchie che sembrano esprimere concitazione ed energia, e un combattimento in atto con e dentro l’immagine: non si sente in certi dipinti come l’eco dello strepito convulso di una lotta tra due galli? E non è come se queste forze in combattimento e in subbuglio fossero la condizione preliminare all’emersione della rappresentazione?

In un libro recentemente pubblicato in Italia che è la trascrizione di un corso universitario di Gilles Deleuze tenuto a Vincennes nel 1981 interamente dedicato alla pittura, il filosofo fa coincidere una svolta nodale nella storia della pittura con una serie di dipinti il cui soggetto è la catastrofe, declinata come tempesta, uragano, battaglia e scontro tra flotte o eserciti. La catastrofe, secondo Deleuze, non è solo un tema della rappresentazione che ricorre da un certo momento della storia in poi. È anche una sorta di abisso in cui precipita il linguaggio. La catastrofe come tema della rappresentazione provoca cioè un inabissamento del linguaggio, dal cui collasso (non cioè da un sistema preordinato, o coerente e organico di rappresentazione), comincia a riemergere la rappresentazione, prima di tutto sospinta dal colore (un colore nuovo, epifanico), poi come forma riconducibile al reale. “Se vedeste un Turner del periodo finale, – afferma Deleuze – accettereste il termine catastrofe. Perché a questo punto vengono in soccorso dei pittori che impiegano proprio questo termine, che dicono: sì, la pittura, l’atto del dipingere passa attraverso il caos o la catastrofe. E aggiungono: soltanto ecco, ne scaturisce qualcosa. La nostra idea è confermata: necessità della catastrofe nell’atto del dipingere affinché ne emerga qualcosa.”

Dunque la forma astratta come gorgo o magma, non è, anche nel lavoro di Luc Ming Yan, un corrispettivo di questa catastrofe, il luogo, o meglio, il caos da cui far emergere tracce di forme nominabili, riconducibili al reale, vagamente descrivibili? In un dipinto come Dream, ad esempio, sembra di veder apparire e delinearsi, in un groviglio di pennellate, i tratti di una testa mostruosa e diabolica; mentre in Meld lo stesso intrico di pennellate rilancia l’impressione di un nugolo vorticoso di ali e piumaggi, di uccelli – soggetto, tra l’altro, che si ripete nella sua pittura. E se in un dipinto come Swap pare di veder affiorare un intreccio di arti o zampe che si aggrappano l’una all’altra, e si afferrano reciprocamente; in Counter Helix le pennellate bianche sul lato sinistro della rappresentazione diventano proprio unghie o artigli, tratti che feriscono, volatili e acuminati. E le figure che sembrano più stabilmente delinearsi in lavori come Magma o Welcome, Happy o L’antihéros – rozze, sgraziate, fumettistiche e al contempo spettrali e preistoriche – non sembrano solo un’evoluzione di quel movimento (o rimescolamento) di forme potenziali che è in atto in quel magma astratto?

In sostanza, cos’è che voglio dire? Che questo viluppo o nugolo è una specie di antefatto, come un luogo di gestazione in cui sembrano aver origine tutte le figure della pittura di Luc Ming Yan. E al contempo, anche quando la figura appare compiutamente, in un primo piano dell’immagine, il magma non si dilegua, e non smette di esistere come paesaggio e habitat delle figure, di lasciare traccia visibile di sé in forma di sfondo pastoso e indeterminato, o partitura di pennellate e macchie più esangui e volatili, tratti “a-significanti e di sensazione” (ancora un’espressione di Deleuze) che punteggiano la superficie qua e là, in alto e in basso. Fin dove arriva la classica separazione tra figura e sfondo in dipinti come L’antihéros o Surprise, in cui ciò che sta dietro sembra anche affacciarsi davanti, cioè dentro o sopra la figura?

Vengono in mente a questo proposito alcuni ritratti tardi di Cezanne – penso al Ritratto Ambroise Vollard o al Ritratto del giardiniere Vallier o al Ritratto di Contadino –, dove si stabilisce una assoluta continuità tra figure e sfondo. Una macchia di marrone, o di verde o di azzurro, può posarsi indifferentemente sul corpo della figura ritratta o nel paesaggio. Questa continuità è stabilità dal colore. I colori esterni, diciamo quelli atmosferici, contaminano anche la figura. E viceversa, come se fossimo in presenza di figure-paesaggio, figure-sfondo.

Anche nei lavori di Luc Ming Yan, attraverso il colore, figure e paesaggio finiscono per appartenere alla stessa atmosfera, contaminandosi e compenetrandosi reciprocamente. In una serie di dipinti che hanno per soggetto alcuni grossi ratti le figure portano su di loro, in primo piano, una porzione di quel colore magmatico e pastoso che sta dietro, come se fossero soltanto escrescenze dello sfondo, con cui continuano a condividere la stessa oscura sostanza e corporeità. E lo scheletro rappresentato in Deux tetes è struttura permeabile, contorno che fa avanzare lo sfondo assieme alla figura, nelle cavità dello scheletro. In altri lavori, invece, lo sfondo è compatto, monocromatico, come nella serie in cui l’artista rappresenta placidi (e minacciosi) gattoni. Eppure, in Xiaokelian, lo sfondo è colorato di un marrone con striature grigie come il manto del gatto, mentre in Liaovi interrogateur figura e sfondo sembrano compenetrarsi in un punto, nell’occhio dell’animale colorato dello stesso giallo. E in un dipinto come Bouc de Topaze figura e sfondo, pur di toni diversi, sembrano condividere la stessa sostanza minerale, e magica in un certo senso. Insomma, esiste una reale distinzione tra figura e sfondo nei lavori dell’artista? Ed esiste un’interiorità, un ipotetico “dentro” delle figure che non sia espresso e reso visibile da ciò che sta loro dietro o attorno?

Un’ultima osservazione: nei lavori di Luc Ming Yan è sempre in atto una ibridazione tra forme che possono indifferentemente appartenere alla cultura pop come alla storia dell’arte, che scorre in sottotraccia in molte immagini. La danza di mostri rappresentata in uno dei lavori esposto a Reggio Emilia, ad esempio, è una variante della più classica danza macabra, un soggetto che si ripete nella storia della pittura. E le immagini rappresentate in molti dipinti hanno un’aria da capricci settecenteschi (in particolare quelli di Goya). E in generale, l’aria e il vento che sembrano spirare in molte immagini, non è la stessa che anima e sconvolge le forme nei dipinti di Tiepolo o Fragonard?

Così nei suoi lavori tutto si svolge all’insegna della rapidità, di un febbrile sussulto, della transitorietà. Molti soggetti sembrano attraversare l’immagine come di passaggio o colti nel mezzo di un attraversamento, come se il movimento che anima i suoi dipinti rendesse i soggetti perpetuamente instabili. Il magma dei dipinti di Luc Ming Yan è anche questo: inarrestabile rimescolamento di forme e figure del dissimile. Luogo di un immaginario che può dar vita a continue metamorfosi, e inediti visionari incontri e dialoghi tra figure apparentemente inassimilabili: un alieno e un pappagallo; un lupo mannaro, un cane e una scimmia; la tartaruga e il palombaro, appunto.

Orari di apertura del Palazzo dei Musei

martedì, mercoledì, giovedì 10.00 – 13.00

venerdì, sabato, domenica e festivi 10.00 – 18.00

lunedì, chiuso

Palazzo dei Musei opening times

Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday: 10:00 am – 1:00 pm

Friday, Saturday, Sunday and public holidays: 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

Closed on Mondays

Luc Ming Yan. The turtle and the diver

Curated by Alessandro Gazzotti, with a written commentary by Davide Ferri

Reggio Emilia, Palazzo dei Musei, 19/12/2024 – 02/03/2025 extended until 9/03/2025

Thursday 19 December at 5:30 pm: Opening of the exhibition Luc Ming Yan. The turtle and the diver. Visions spanning nature and painting in Palazzo dei Musei.

Constant interplay between archaeology, art, photography and science is one of the main objectives of the new Palazzo dei Musei. The museum collections will be harnessed to open up the endless variety of narrative, poetic and scientific opportunities that they can offer to contemporary culture. Taking the view that artists can use the collections of the City Museums as analytical tools and sources, just like scholars and experts in various other fields, Palazzo dei Musei is promoting forms of collaboration that will inspire breathtaking new outlooks.

On this front, the young French artist Luc Ming Yan’s reaction to our museum – and the zoological, anatomical and Spallanzani natural history collections in particular – immediately sparked a great deal of interest. This subsequently took concrete form in an exhibition that encourages reflection and opens up dialogue between nature and painting.

Curated by Alessandro Gazzotti, the exhibition presents 48 oil paintings on canvas by the artist, who was born in Dijon in 1994 and works in Paris and Shanghai. With his distinctive approach to colour and vast range of styles, Yan is an original player on the contemporary painting scene. There will be direct, thought-provoking interaction between the works and the natural history collections, especially the large fossilized remains of “Valentina” the whale, a key find from the local area that dates back to the Pliocene. A written commentary for the exhibition has been provided by art critic and curator Davide Ferri, who teaches at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna and was appointed a few weeks ago as the new artistic director of Arte Fiera. Ferri is a huge admirer of Yan’s work. He writes: “Luc Ming Yan’s work is like a musical score that expands from one room to the next and combines two different sides. Some works present a jumbled, erratic kernel of frenzied, lively and contrasting brushstrokes.

Others are clearly figurative works depicting animals (such as rats, birds, monkeys and cats), skulls, metamorphic figures and aliens that have something vaguely grotesque about them and seem to be influenced by manga or pop images. In addition, pre-figural elements and scraps of shapes (such as paws, horns and sharp claws) may appear within abstract paintings, in positions around the edges or just outside the fertile, generative jumbled masses and giving the impression that they are emerging from them. It is as if a battle were taking place in these works. All the shapes and figures in the paintings seem to stem from the nervous energy on the surface.”

Luc Ming Yan (1994, Dijon, France) is a French painter who lives and works in Dijon. He won the Ernest Manganel Award and studied at the ECAL University of Art and Design in Lausanne, Switzerland. Since he graduated, his paintings have been displayed internationally. Recent exhibitions include: Abstraction (re)creation – 20 under 40, Le Consortium, curated by Franck Gautherot and Seungduk Kim, Dijon, France (2024); The Drawing Centre Show, Le Consortium, curated by Franck Gautherot and Seungduk Kim, Dijon, France (2022); Ipotesi Astronomiche, Villa Flor, S-chanf, Switzerland (2021); Stasi Frenetica, Artissima Unplugged, MAO – Asian Art Museum, Turin, Italy (2020). In 2024, Yan’s works Midnight (2023) and Time Walk (2023), as featured in the Abstraction (re)creation – 20 under 40 collective exhibition, became part of Le Consortium’s permanent collection.

It might be said that there are two sides that can be seen to Luc Ming Yan’s works. This is especially true of those in the exhibition entitled The turtle and the diver at the Reggio Emilia City Museums. On one side, there are paintings that I can only describe as abstract, with clumps of colour and thick, unsettled brushstrokes moving in many directions and swirling around the centre of the image. On the other side, there are more clearly figurative works depicting monstrous creatures, aliens, metamorphic figures, anthropoids and animals (either wild ones such as rats and birds, or tame ones like cats and chickens), or simply pop and fantasy characters that might be found in comic strips, anime or video games. Reflecting this, the exhibition in Reggio Emilia unfolds like a musical score and what appear to be two separate sides of the artist’s work go hand in hand from the first room to the last.

It is worth noting here that as soon as I used the words “abstract” and “figurative” at the start of this commentary, I realized how obsolete they sound. Should these two long-established categories still be contrasted with each other? Is it simply inevitable in discussions about painting? Would it not be better to state right from the start that for some decades now, a number of painters – including Luc Ming Yan – have highlighted the porous nature of the boundaries between them and brought the categories closer together? They can even be overlapping and interchangeable.

The premises hosting the exhibition in Reggio Emilia could hardly be further from a white cube. Part of the exhibition is actually inside the display cases and in general there are strong connotations due to the close proximity to the collections, which are of a highly specific nature and cover fields such as natural history, anatomy, botany and ethnography.

Containing taxidermied animals, bones, skeletons and various kinds of finds, they are like a Wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities. Luc Ming Yan almost seemed to be inspired by the variety. For example, the figures in his paintings might be common or prehistoric, imaginary or extinct, deformed and bizarre (like a dinosaur skeleton with two skulls), but in general there is a place for them all in this bestiary. In addition, there is a palpably threatening feeling in some of Yan’s paintings, along with a number of overt references to death: several works depict skulls, while a dead sparrow is portrayed prominently in another, alongside a black cat that was presumably behind its demise. The exhibition takes its name, The turtle and the diver, from a painting showing a turtle and a diver coming face to face at the bottom of the sea. The diver looks helpless and possibly dead. His head and diving suit are clearly slumped. His body is bloated and the palm of one hand is facing upward, in what looks like a sign of surrender. In a kind of role reversal, the turtle seems to be exploring and approaching to take a look at the outsider.

Now let us go back to abstract paintings. Above I have described a number of the subjects shown in the exhibition, but the really crucial point to consider is that as onlookers gradually grow accustomed to Luc Ming Yan’s paintings, these two sides to his work – abstract and figurative – start to seem like communicating vessels. In some respects, they begin to appear much closer than they do at first sight.

As I stated above, each of his abstract paintings is a swirling clump of colours and unsettled brushstrokes moving in many directions. They tend to build up in layers in a central mass, or stretch vertically or diagonally across the surface. The hordes of brushstrokes, colours and dabs of paint seem to convey excitement and energy, not to mention a battle with and within the image: it might be said that the frenzied roar of a cock fight seems to ring out in some of Yan’s paintings. Does it not feel as if it is this conflict and commotion that lays the foundations for the portrayal to emerge?

In Vincennes in 1981, Gilles Deleuze taught a university course all about painting, the transcript of which was recently published in a book in Italy. In it, the philosopher tied together a key turning point in the history of painting with a series of paintings whose subject was catastrophe, in the form of storms, hurricanes, battles and clashes between fleets or armies. According to Deleuze, catastrophe is not just a topic that begins to recur after a certain point in history. It is also a sort of abyss into which language plunges. In other words, depicting catastrophe sends the language swiftly downhill. It is what is left after this collapse (rather than a pre-established, or coherent and organic portrayal system) that provides the starting point for the re-emergence of portrayals. It is driven first and foremost by colour (a new epiphanic colour), then by forms that can be traced back to reality. “If you were to look at a late Turner, you would accept the term catastrophe,” states Deleuze. “That’s because it was at that time that painters began to use that very term. They affirmed that the act of painting takes place through chaos or catastrophe. And they added that it gives rise to something. This confirms our idea: catastrophe is needed in order for something to emerge from the act of painting.”

So could we not say that abstract shapes – such as the jumbles and maelstroms seen in Luc Ming Yan’s work – amount to another example of the catastrophes and places – or rather the chaos – from which elements emerge of forms that can be named, traced back to origins in reality and vaguely described? For instance, in his painting Cream the features of a grotesque and vaguely diabolical head seem to appear and take shape in entangled brushstrokes. Meanwhile, in Meld a similar web of brushstrokes creates the impression of a mishmash of the wings and plumage of birds, which are a recurring subject in Yan’s paintings. In Swap interwoven limbs or paws appear to be grabbing and clinging onto each other, while the white brushstrokes on the left side of Counter Helix become sharp, scratching and volatile nails or claws. Then there are the figures that appear to take shape more stably in works such as Magma, Welcome, Happy and L’antihéros: crude, ungainly, vaguely grotesque and comic strip-like, with something spooky and prehistoric about them. Do they not just feel like a more evolved form of the movement (or mixing) of potential shapes in the abstract jumbles?

Essentially, what I am trying to say is that this tangle or cloud is a sort of first step; a place for gestation from which all of the figures in Luc Ming Yan’s paintings seem to spring. Even when complete figures appear in the foreground of an image, the jumble does not fade away. It takes the shape of a landscape or habitat for the figures and remains in view as a hazy, fuzzy background, or a score of paler, more ephemeral brushstrokes and marks that have more “feeling than meaning” (to quote Deleuze again) and are dotted across the surface, at the top and bottom. Where can the traditional dividing line between the subject and the background be drawn in paintings like L’antihéros and Surprise, in which what lies behind also seems to stretch forward and reach inside or over the figures?

This aspect calls to mind some of the late portraits by Cezanne in which the subjects and backgrounds blend into one. For instance, take Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, Portrait of the Gardener Vallier and Portrait of a Peasant. A dab of brown, green or light blue might be placed without distinction on the body of the subject or in the background. Colour establishes continuity. The external colours – which might be deemed atmospheric – spread onto the subjects. The opposite is also true, resulting in figures that are almost part landscape or background.

Similarly, in Luc Ming Yan’s works colour makes the figures and landscapes into part of the same atmosphere. They intermingle and permeate each other. Take the series of paintings of big rats. Some of the muddled, hazy colour from behind can be seen on the subjects in the foreground. They almost appear to be nothing more than offshoots from the background, still made of the same obscure matter and substances. The skeleton in Deux tetes is a permeable framework. The background reaches through its outline into the figure and the gaps between the bones. In contrast, in other works the background is solid and monochromatic. This is the case with the artist’s series of paintings of big, calm (but menacing) cats. All the same, in the brown background of Xiaokelian there are grey stripes like in a cat’s coat, while the figure and background in Liaovi interrogateur seem to merge in one point, due to the yellow hue of the animal’s eye. Although the figure and the background in Bouc de Topaze are in different tones, they seem to have the same mineral – and in some respects magical – substance to them. So can a real distinction be drawn between the figures and the backgrounds in the artist’s works? And in the figures that he paints, is there an inner side and something hypothetical within that is not conveyed and made visible by the backgrounds?

One last remark: in Luc Ming Yan’s works there is constant cross-fertilization between forms that could just as easily be part of pop culture or the history of art, which lies hidden in many images. For example, one of the works on display in Reggio Emilia shows dancing monsters. It is a fresh take on the classic Danse Macabre, which has a long history behind it in the art world. Many of the images in Yan’s paintings also call to mind 18th century capriccios, especially Goya’s Caprichos. More generally speaking, are the air and wind that seem to blow in many pictures not highly reminiscent of those that ruffle and breathe life into the forms painted by Tiepolo and Fragonard?

In Yan’s works, everything is steeped in a sense of swiftness, feverish agitation and transience. Many subjects seem to have been depicted as they were moving across or passing through the image. The movement in the paintings gives the subjects a feeling of perpetual instability. Another aspect of the jumble in Luc Ming Yan’s paintings is an unstoppable mixing of different forms and figures. It is a place where his imagination can conjure up constant metamorphoses and unprecedented, visionary encounters and dialogues between seemingly incompatible figures: an alien and a parrot; a werewolf, a dog and a monkey; and of course a turtle and a diver.

Opening

Venerdì 19 dicembre ore 17.30

Palazzo dei Musei

Galleria fotografica

L’iniziativa è ad ingresso gratuito e senza obbligo di prenotazione

Info:

0522 456816 Palazzo dei Musei, via Spallanzani, 1

Durante gli orari di apertura della sede.

musei@comune.re.it